During the terrorist attacks in Norway 22nd of July 2011, 77 persons were killed and many more injured. The attacks led to massive, multifaceted efforts of civil society, especially concerning the attacks at Utøya. The officially appointed investigation commission acknowledged that more lives had been lost if civilians had not taken spontaneous action and helped rescuing victims from the island during the attack, providing crucial information to the official emergency responders and assisting transporting the SWAT team to the island.

In the aftermath of the terror attacks a public investigation was carried out, scrutinizing Norwegian authorities’ prevention, preparation, and response actions. Several research initiatives have been carried out, addressing both formal crisis management dimensions and the long-term consequences for victims and next of kin. However, the role of the spontaneous volunteers does not seem to have received the same level of attention in the ten years that have passed since the attack.

Spontaneous volunteering not addressed in research related to the attack

In ENGAGE, we want to understand not only authorities’ actions in resilience and crisis response, but also the role of ordinary citizens. Therefore, we decided to look closer into the characteristics of the academic articles on the Utøya attack: Were there any scientific efforts directed towards volunteer efforts during and immediately after the attack? We conducted a literature search in various sources and found 154 peer-reviewed items. The short answer is that we found only one relevant article explicitly studying the role of the spontaneous volunteers. This is somewhat surprising, given that the spontaneous volunteers have been highlighted as “heroes who saved the day”, when the efforts of some of the formal organizations failed in several areas. The volunteers have received praise from the official investigation commission, and some have been given medals of honour. Still, their role, contributions and motivations seem to have been largely ignored as a source of knowledge about resilience toward extreme events.

The contributions of spontaneous volunteers

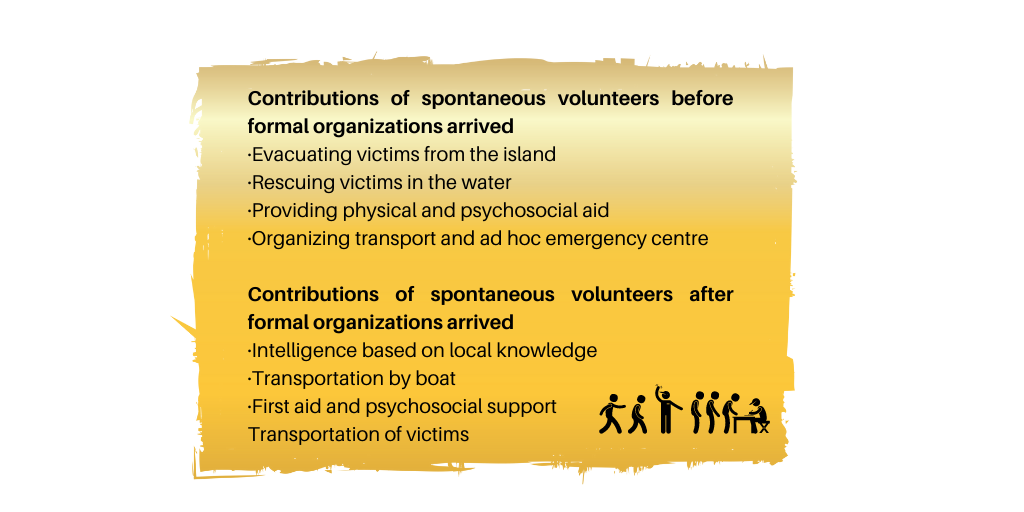

Through a document-based investigation in ENGAGE we have obtained a preliminary overview of spontaneous and voluntary actions taken during the attack. These contributions included: 1) evacuating victims from the island by boat, 2) distributing life jackets and rescuing victims by boats in the water during gun fire, 3) providing physical and psychosocial first aid, 4) organizing ad hoc emergency care centre and transporting victims to hospitals and an initially ad hoc emergency centre at a nearby hotel. This is a crucial chain of response actions that emerged spontaneously and informally, before any formal emergency organizations arrived at the disaster area.

With the arrival of the different emergency services, volunteers offered and provided their assistance. This included 1) intelligence based on local knowledge, 2) transportation by boat, 3) first aid and psychosocial support, 4) transportation of victims to the positions of ambulances, emergency centres and hospitals. In the immediate aftermath of the attack (after the perpetrator has been captured) both convergent non-affiliated and affiliated volunteers showed up at official emergency centres offering services like psychosocial support and administrating the registering of victims. In this phase, the volunteers, and their resources, move into being a support function for the formal first responders.

What does this case tell us about societal resilience?

We believe studying the role of spontaneous volunteers can generate important knowledge for future disasters. The spontaneous volunteering during and after the Utøya attack is a kind of societal or community resilience – meaning here the citizens’ ability to self-organize and adapt – when faced by major disasters. There is need for a more elaborated conceptual apparatus for understanding the factors involved how, when and why ordinary citizens sometimes become crucial resources for resilience. In the following we provide some intuitive categories that help to explain this.

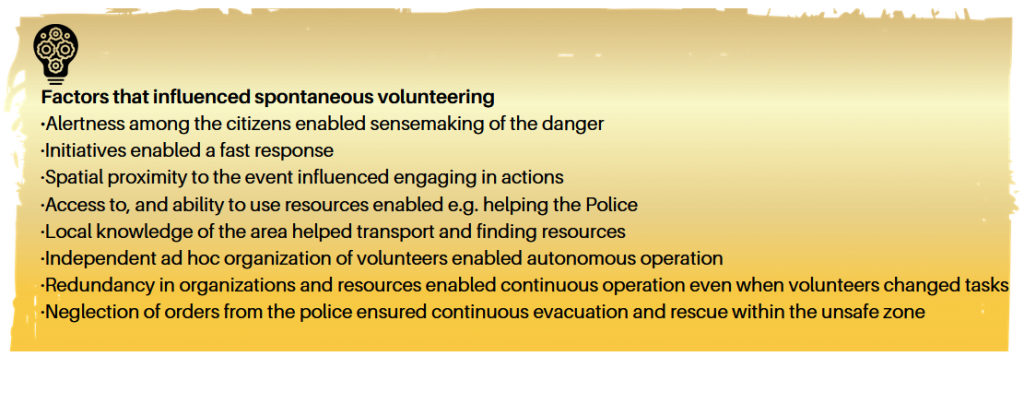

There seems to have been an alertness among the volunteers due to information about the first attack in Oslo. This might explain both the outcome of the volunteers sensemaking when they heard about and/or observed unusual activity on the island, and their willingness to act on this knowledge. Community alertness and initiatives taken by individuals inclined to act seem to have been a prerequisite for the fast response among the volunteers. The same applies to the spatial proximity to the attack. The spatial proximity had probably an impact on the outcome of the volunteers sensemaking and their choice of adequate actions. Access to resources and the ability to utilize resources relevant in the specific situation (such as boats, life jackets, showers, buildings, clothing, cars were essential) was decisive for the type of tasks that could be performed by the volunteers, as well as providing necessarily resources for the police (boats). Local knowledge among the volunteers regarding accessible resources (equipment and personnel) contributed to the efficiency of the operations. Intelligence based on local knowledge about the local geography was also crucial for giving the Police ability to efficiently localize and navigate to the island. Established social bonds between individuals was important for both recruiting more personnel and to establish efficient ad hoc emergency organizations. Several independent ad hoc organizations of volunteers with limited coordination contributed to focus on handling tasks based on the volunteer´s situational awareness in the area they were operating. This contributed to fast tactical adaptions to the perceived needs in the area they were operating. Further, the redundancy in both organizations and task performance did ensure efficient the continuation of certain tasks in cases when volunteer resources were reallocated to new tasks (due to their own choice or due to commands from formal organizations). The neglections of orders from the police to evacuate from the area, meant that rescue operations continued, and that several lives among the escaping victims was saved. The spontaneous volunteering of brave citizens saved many lives that day. However, they put themselves in potential danger and experienced traumatic events. This illustrates that citizen intervention in disasters is a double-edged sword, representing several dilemmas without a clear normative answer. Nevertheless, if we wish to understand disasters and societies’ resilience capabilities toward disasters, these actions cannot be ignored in neither public investigations nor research. They can provide important lessons, not only about disasters and resilience, but about the societies in which disasters take place.

The spontaneous volunteering of brave citizens saved many lives that day. However, they put themselves in potential danger and experienced traumatic events. This illustrates that citizen intervention in disasters is a double-edged sword, representing several dilemmas without a clear normative answer. Nevertheless, if we wish to understand disasters and societies’ resilience capabilities toward disasters, these actions cannot be ignored in neither public investigations nor research. They can provide important lessons, not only about disasters and resilience, but about the societies in which disasters take place.

Authors: Asbjørn Lein Aalberg (SINTEF Digital), Rolf Johan Bye (SINTEF Digital) & Stian Antonsen (NTNU Social Research)